Introduction

Continual revolutions within the world of the industry have often driven transformations within higher education. In a recent employer survey of the Hong Kong Education Bureau in 2019, only 63% of employers anticipated that graduates would have to have a degree in order to obtain a job. The employers focused on employees’ affective traits and work-related characteristics, such as their willingness to work collaboratively, being innovative, and being active problem-solvers [1]. To meet the changing demands of the industry, there has been a gradual shift of university concentration to positive youth development in recent years, leading to a rising number of whole-person development courses added to the curriculum. Research has shown that these courses could facilitate students’ intrapersonal competence, and work-integrated learning (WIL) [2,3]. This new page of higher education was named the era of education and industry 4.0 [4]. Salmon added that the era of education 4.0 relies on advanced technologies for personalizing students’ learning needs with anticipated enhancement on employability skills.2020 was a year marked by dramatic changes in education because of the global COVID-19 pandemic. As a result of lockdown and social distancing, course instructors reformed their courses with a blended learning approach for sustaining quality teaching and learning. Through the enhancement of technologies, research has demonstrated the impact of the blended learning approach on students and faculty members for yielding satisfactory outcomes [5,6,7]. Blended learning comprises a technological environment that fosters flexible and personalized learning [8] and therefore enables educators to match students’ profiles with an appropriate educator for facilitating learning outcomes [9]. Prior research in the United States showed how to adopt first year quantitative and qualitative data of a career development course to refine their second year learning content for enhancing career decision-making self-efficacy with a larger effect size [10]. This finding calls for the potentials of linking research and practice in the design of a career development curriculum. In Hong Kong, the development of WIL is still in its early stages [11], not to mention WIL in blended or online learning modes. There is a pressing need to carry out evidence-based practices to assess the program effectiveness.

Literature Review

Previous Findings on the Career Development Program

Over the past two decades, best practices to enhance program effectiveness of traditional career courses have been well documented (e.g., Ryan 1999 [12]). According to Ryan’s work, the best practices of traditional career program comprised five elements named “critical components”. These critical components were developed based on the findings from 62 studies and over 7000 participants on career choice outcomes. When the career program contains one or more of these critical components, a significant enhancement of effect size was obtained [13]. These critical components are workbooks or written exercises, individualized interpretations and feedback, world-of-work information, modeling, and attention to building support [14]. In general, career program from past studies demonstrated a small effect size [14]. As the general goal of the career program in the 21st century aims to facilitate clients to have job changes without losing a sense of self and social identity [15], the researchers chose to evaluate participants’ self-concept development as a parameter to decide its effectiveness. The outcome measurements showed participants’ vocational identity, career-decision making efficacy, perceived career barrier, and career adaptability [16,17,18]. The effectiveness of career programs has been investigated for almost two decades [13,19]. However, a recent meta-analysis indicated that most of these studies only report the effects of face-to-face sessions.

Transforming Asynchronous and Synchronous Career Development Program

The rise of technologies and the internet has brought educators with innovative opportunities to evolve the teaching pedagogy and renovate the traditional face-to-face learning model into one of the more engaging and effective learning nature. Despite the growing number of career courses on massive open online course (MOOC) platforms [20], very little research on the effect of career courses has been conducted in the blended learning mode. We conducted a literature search in October 2020 to review the empirical studies of asynchronous and synchronous courses of career development for late adolescents. A total of five electronic databases, namely ProQuest, PsycINFO, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were searched with keywords of “Online Career Course/Intervention”, “Blended Learning Career Development Course”, “Massive Open Online Career Course” and other combination of these keywords. The searches returned only a small number of studies concerning this scope in the period of 2016 and 2020. Among these studies, one recent study of Iran demonstrated that online course yielded a similar effect to face-to-face program but it was about individual counseling [21]. Another study addressed whether MOOC enhances learners’ employability but the samples were not specific for young students [22]. The remaining studies lack either validated scales to measure the effectiveness or a clear research framework of the investigation. Our systematic searches have shown that there is a gap in the scholarly literature in the studies related to Asian or Chinese samples.

Theoretical Background of Key Indicators for Examining Courses Effectiveness and Personalize Learning

Core Self-Evaluation (CSE)

Massive empirical evidence from western countries showed the relationships between personality traits, job performance, and job satisfaction [23,24,25]. As personality theories are one of the modern vocational theories, core self-evaluation (CSE) theory has been a prevalent topic of investigation by industrial and organizational psychologists. The theoretical basis of CSE refers to a person’s stable trait and how she/he perceives the overall evaluation of herself/himself, the worthiness, and capability to handle tasks that explain the relationship to the environment [23]. The CSE is the combination of four traits, including locus of control (i.e., the belief in self-control over the situation); neuroticism (i.e., emotional stability); self-efficacy (i.e., the belief in one’s ability to perform well); and self-esteem (i.e., the general evaluation of own merit). A positive CSE generally emphasizes positive overall evaluation within those people who had high confidence for their capacities to complete tasks and achieving desired outcomes [26]. CSE is defined as adaptive readiness which is the psychological trait of willingness to deal with occupational transitions [27], and has a positive impact on other career adaptive responses, such as career decision self-efficacy [28], vocational identity [29], job satisfaction [30], and career adaptability [31].

Career Adaptability

According to the career construction theory [32], career adaptability concerns how an individual copes with his/her new working environment by a sequence of changes in an individual’s readiness, psychosocial resources, responses to condition, and outcomes of response [33]. It emphasizes how a respondent adopts his/her psychosocial resources for switching occupational environment and handling difficulties at work. By using the ABCs models (attitudes, beliefs, and competencies), those coping behaviors were categorized into four dimensions, including: (1) thinking about the future career, (2) increasing control for future career, (3) becoming curious about new career opportunities, and (4) confidence to pursue one’s career goals [33]. Rodolph, Lavigne, and Zacher [34] conducted a meta-analysis and summarized 90 past studies for explaining the positive associations between CSE and career adaptability. These adaptive traits and resources could exist across time for predicting individual’s work success, identity formation, and performance.

Vocational Identity

Based on the idea of the career construction model of adaptation [34], the ultimate outcomes of career adaptation behaviors are helping people to confirm their career identities. Identity crisis is one of the exciting research fronts in developmental milestones. Psychologists proposed two mainstream theories on that, namely, Erikson’s psychosocial theory [35] and Marcia’s identity status theory [36]. While psychosocial theory focused on the lifespan identity formation, Marcia’s theories were designed to have alternative commitments in terms of occupational, sexual orientation, and political points of view for late adolescence which is more flexible for vocational research. The vocational identity, proposed by Marcia and other scholars [36,37] indicated that an individual’s occupational status could be shaped by a 2 × 2, commitment vs. exploration matrix. The presence or absence of the exploration and commitment to the career could lead an individual going through different stages. They are the identity diffusion (avoid exploring and making career commitments), identity foreclosure (commitment on a career is made without exploring alternatives), the identity moratorium (career commitments are absent but actively discovering alternatives), and the identity achievement (commitment on a career is made with exploring alternatives). According to Marcia, identity formation generally goes through from diffusion, moratorium to achievement. Concerning the contribution of these variables to the development of career program, it is necessary to examine the linkage between the theoretical background and the practical implications.

Purpose of the Study

The association of CSE, vocational identity and career adaptability have been well studied. However, a recent meta-analysis revealed that there were only four studies addressing the individual differences in program effectiveness, and less than 60 studies related to career programs in the past 20 years [13]. Most of the studies on career adaptability only compare between group differences and measure the effect at a single time point [34]. This paper aims to contribute to the debate on the effect of a blended career program and the effects of personalized learning.Most of the previous studies on the effects of CSE in career program were conducted in the Western countries, studies from Asian samples are scant. In view of the limited studies examining career awareness in Hong Kong, the need to assess the effectiveness of different modes of career program is warranted [38]. Earlier evidence about CSE assumed that the stable traits (locus of control, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and neuroticism) could occur across the lifespan of the individuals [39,40] but it also shows cultural differences [26]. However, recent studies have shown that CSE is a trait with a malleability that could be modified over time by interacting with personal experience [41]. For instance, a low self-esteem was shown in Asian samples in a cultural study [42]. The Hong Kong samples were the second lowest in self-efficacy compare with other 24 countries [43]. While Asian samples often report a relatively negative self-perception together with greater academic [44,45] and work accomplishments [46] in the world, it would be inspiring to examine these dynamic relationships of adaptivity and adaptability among the pre-working Asian labor force. Although evidence pointed to the association between CSE, vocational identity and career adaptability, the application of these findings for designing a career program is still a big void, especially in non-occidental samples. The effectiveness of career program in the format of blended learning also warrants greater attention as it helps examine its effectiveness to face the challenges of the pandemic era successfully and welcoming the era of Education 4.0. In light of these concerns, the objectives of the present contribution are to: (1) examine the effects of a seven-week career development course in the blended learning mode; (2) examine the role of distinctive core personality patterns in the effectiveness of the course; and (3) explore any cultural and gender differences of CSE, occupational identity, and career adaptability in young Asian adult samples. This is amongst the first effort in evaluating the effectiveness of a career course in blended learning mode during the COVID-19 pandemic within the university setting. It is anticipated that the use of outcome data in this study could shape the directions for educators to tailor-make students’ learning content during the course construction phase. We anticipated the study results could shed light on the cultural specificity of the conceptual framework of the career construction model.

Conceptual Framework in this Study

In this study, we adopted a conceptual framework based on the career construction model of adaptation [15,34] (Figure 1). This conceptual model explained the associations among adaptability readiness (core self-evaluation), adapting responses (career adaptability), and adaptation results (vocational identify). Pre-test scores of these adaptability indicators were set as covariates. It is expected this model would be used for validating the effectiveness of the proposed course.

The Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and Research Hypotheses

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, educators worldwide were required to re-form learning objectives and adopt online learning technologies. To sustain teaching quality and learning outcomes, this study could be one of the touchstones to examine the effectiveness of a career course. In doing so, we sought to contribute to our growing understanding of how and to what extent of a blended learning approach is beneficial to career program design amidst this challenging period. It is hoped that the study would encourage teachers not only to seek solutions for delivering content during the pandemic but also concern personalized learning by adopting the latest technology. The hypotheses are as follows:

Hypotheses (H1):There will be a significant difference between pre-test and post-test occupational identity scores.

Hypotheses (H2):There will be a significant difference between pre-test and post-test career adaptability scores.

Hypotheses (H3):For different groups of learners, different combinations of personality traits will emerge based on person-centered analyses. There will be significant main effects of personality traits on post-test occupational identity scores controlling for pre-test scores.

Hypotheses (H4):For different groups of learners, different combinations of personality traits will emerge based on person-centered analyses. There will be significant main effects of personality traits on post-test career adaptability scores controlling for pre-test scores.

Materials and Methods

Research Design and Participants

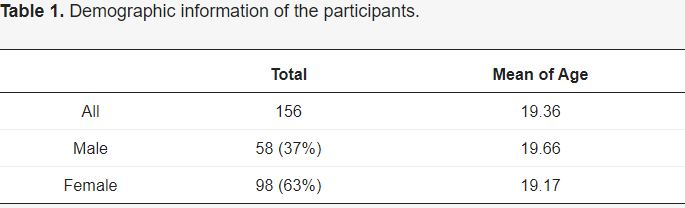

This study adopted a quasi-experimental design. It included pre-test and post-test within-subject measurement. All participants came from a medium-sized University in Hong Kong. In the spring 2020 semester, 162 students had completed pre-test, post-test, and the career course. All participants were associate degree freshmen. The sample included 63% females (N = 98) and 37% males (N = 58) with the mean age of 19.36 (Table 1). The ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Hong Kong Baptist University. The participation was voluntary with no compensation and the participants could opt out at any point of the study.

The Career Course in Blended Learning Mode

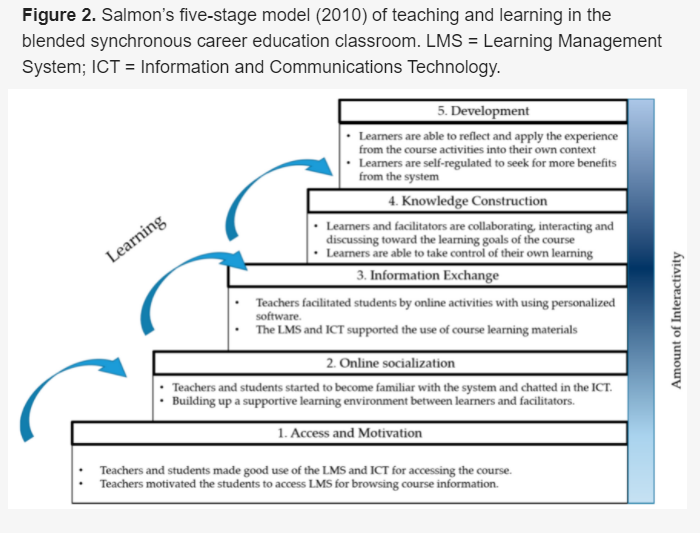

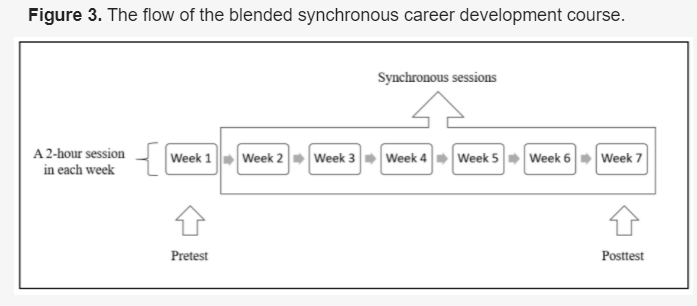

The career development course aimed to assist sub-degree students to articulate into academic programs and explore their career pathways. Students attended a two-hour face-to-face session weekly for 7 weeks. The assessment was continuous including pre-class online exercises, in-class discussions, curriculum vitae with peer assessment, and mock interviews. Upon the completion of the course, students were expected to be able to identify basic elements of personal statements, curriculum vitae for universities, and jobs application, understood their values for the job, gained basic career aspirations, and enhanced their employability skills.In response to the social distancing measures due to the pandemic, the course was transformed from the face-to-face into the online context by adopting the framework of blended learning at the beginning of 2020. Salmon’s five-stage model for online learning [47,48] was adopted to outline the teaching and learning (Figure 2). It is a process-based teaching and learning framework which has been widely applied for scaffolding a steady developmental process in online teaching and learning environment since 2000. In brief, Stage 1 is the course technical cornerstone that sets up a stable stage for learners to participate effectively. Facilitators are e-moderators to encourage learners to explore within the platform. The facilitators made use of the Learning Management System (LMS), Moodle and Information and Communications Technology (ICT), Zoom to deliver asynchronous and synchronous content respectively. The LMS, Moodle is the gate entrance for the students to retrieve their synchronous course room links (supported by the ICT, Zoom), course materials and other asynchronous content. For instance, students can login to the LMS for accessing pre-reading materials and online exercises in the course. After the students click the ICT links during the scheduled class time, it would lead them to join the virtual classroom. The facilitators could therefore make use of the virtual classroom to facilitate student’s engagement in the synchronous sessions such as breakout rooms for group discussions, and chatroom for answering students’ questions. After learners began to familiarize with the platform, they were able to socialize and communicate within these platforms. The interactive experience is generally raised from intrapersonal in Stage 1 to interpersonal experience in Stage 2 [45]. A supportive environment was built by the students and teachers. Personalized learning was fostered by the course’s online activities within the environment. As this course emphasized students’ personal growth especially in career development, each student at Stage 3 and Stage 4 had a unique experience by the e-tivities. The e-tivities were similar to the previous outline of the face-to-face course but transferred into, for examples, separate discussions via Zoom, and online mock interviews with recording. Facilitators also provide a self-directed search inventory, which is a career interest test for the students and asked them to match their personality traits with specific working types and jobs in a synchronous group discussion. Lastly, after participation in the e-tivities, students reflected on their learning. They were self-regulated to seek more information based on their interests. It encouraged students’ career exploration in Stage 5. Table 2 shows the course activities based on Salmon’s framework and Ryan’s critical components. Figure 3 shows the flow of the blended synchronous career development course.

Implementing the Model and Components

The course in blended mode was delivered in the original scheduled time. In practice, the course was set on Moodle as the Learning Management System and Zoom as the video conference platform. Learning materials such as workbooks and class interactive activities were on Moodle to facilitate the blended mode of learning (See Table 2). In each lesson, the educator was to complete the learning activities on a specific topic. For example, the learning objectives of one lesson were to understand the importance of career planning and Holland’s career theory. Besides learning the theoretical background of Holland’s theory [49], the students would also complete an online assessment on O*NET Interest Profiler (https://www.mynextmove.org/explore/ip accessed on 22 January 2020 and 12 February 2020) for their Holland’s codes. The code would be used to identify the personality and interest in career of the students. Holland’s career theory posits how people and work environments can be matched with each other in six different categories-Realistic (R), Investigative (I), Artistic (A), Social (S), Enterprising (E), and Conventional (C). The results generated by O*NET Interest Profiler and Occupation Quick Search (www.onetonline.org (accessed on 22 January 2020)) would indicate which categories are of the student’s top career interests and the corresponding occupational attributes required. Then, they may further explore what potential occupations to follow. Other topics were delivered in a similar way in the blended synchronous career education classroom. The other links to external resources are available to students through Moodle and Zoom. For example, the instructors would guide the students in class time to “Studential” website (https://www.studential.com/ accessed on 5 and 12 February 2020), which contains samples of personal statement for students to apply for different organizations (World of work information). The students can select the appropriate samples as their reference to prepare their personal statements. The instructors would therefore facilitate discussion during the class time for embodying the Online Socialization and Information Exchange stages. Apart from the interactive activities during the class, the teaching team prepared interactive flipped learning video before each lesson. The teaching team inserted questions into video by making use of the e-learning platform Edpuzzle (https://edpuzzle.com/ accessed on 22 January and 5 and 12 February 2020) for raising students’ interests toward the topics. Edpuzzle is supported within the LMS. The flipped learning elements focus on the common mistakes and room of improvement in writing a personal statement, curriculum vitae and attending an interview. Towards the end of the course, virtual mock interviews were arranged for the students.

Measurement

Vocational Identity

The Vocational Identity was measured by the Occupational Identity Scale [37], which is a 28-item, 5-point Likert self-report scale. It consists of four subscales: Achievement (e.g., “After many doubts and considerations, I have a clear idea as to what my occupation will be”), Moratorium (e.g., “At the present moment, I do not know exactly what I want as my career, but I am examining several occupational options”), Foreclosure (e.g., “The occupation I have chosen is a tradition in my family and I feel I would like to follow the family tradition”), and Diffusion (e.g., “At this point, I am not worried about the type of job I will be most successful in; I will think about it in the future”) (Appendix A). The internal consistency of this scale and subscales was satisfied in this study (α > 0.75).

Career Adapt-Ability

The Career Adapt-Abilities Scale (CAAS) is a 4-factor, 24-item self-report scale based on the Career Construction Theory [15,33,51] (Appendix A). The 24 items are divided equally into four subscales (Concern, Control, Curiosity, and Confidence) that measure the adapt-ability resources. Participants answered using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not strong) to 5 (strongest), with higher scores indicating higher levels of career adaptability resource. The internal consistency of this scale and subscales exhibited excellent alpha in the present study (α > 0.80).

Core Personality Traits

Core personality traits [52] were measured by the core self-evaluation scale (CSES) (Appendix A). It is a 12-item self-reported scale with a 5-point Likert scale for illustrating respondents’ traits into 4 stable traits across a lifetime [53]. The constructs were self-efficacy, self-esteem, emotional stability (Neuroticism), and the locus of control. A person with a high level of CSE is characterized as positive, self-confident, well adjusted, efficacious, and capable of controlling one’s volitional actions [46]. In the present study, the scale exhibited acceptable to satisfied alpha (α > 0.70). Only the locus of control scale performed poorly (α < 0.50) and was excluded from the analysis.

Procedure

The study has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hong Kong Baptist University. Participants were given a link to an online survey that was programed using Qualtrics® [54] survey platform both at the beginning and end of the course. Participants volunteered for the study. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents. 162 participants had completed both pre- and post- tests and they were included in the data analysis of the study. The participants needed about 15 min to complete the questionnaire.

Data Analysis

The analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS 26 software [55]. 6 outliers were excluded from the analysis because of their significantly shorter or longer response time for completing the survey. The effectiveness of this blended learning course was investigated using the variable-centered and person-centered approaches.

Variable-Centered Approach

In this approach, the population under the study was considered as homogeneous. A paired-sample t-test was used to examine the general effectiveness of the 7-week course on occupational identity and career adaptability among all participants. The stability of CSE was tested to confirm no changes across time and course.

Person-Centered Approach

The second step of the analysis was based on the person-centered approach. This approach offers a comprehensive investigation to individual differences, it focuses on how specific combinations of variables that could be found in different subgroups interacted to shape behavior [56,57]. From a vocational research perspective, a common example could be using personality traits to predict job performance. The k-mean clustering analysis [58] was used to classify the learners. K-means clustering is one of the non-hierarchical data clustering approaches that classifies data into different subgroups [59]. In this study, students contain the same CSE combinations were clustered into one group and the students with different CSE combinations were distributed to other groups so that the data in one group have a slight degree of variance. The clustering measures for the K-means process were as follows: (1) decide the numbers of k-clusters; (2) allocate initial values of random numbers to cluster centers; (3) allocate data to the nearest cluster. The Euclidean distance was used to distance all data to each cluster center point. As a result, learners with a distinctive combination of CSE would be classified.Lastly, by controlling the pre-test results, a two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to determine a statistically significant difference between the personality traits, gender, or other possible personal particulars on the occupational identity, and career adaptability.

Results

General Effectiveness of the Career Course

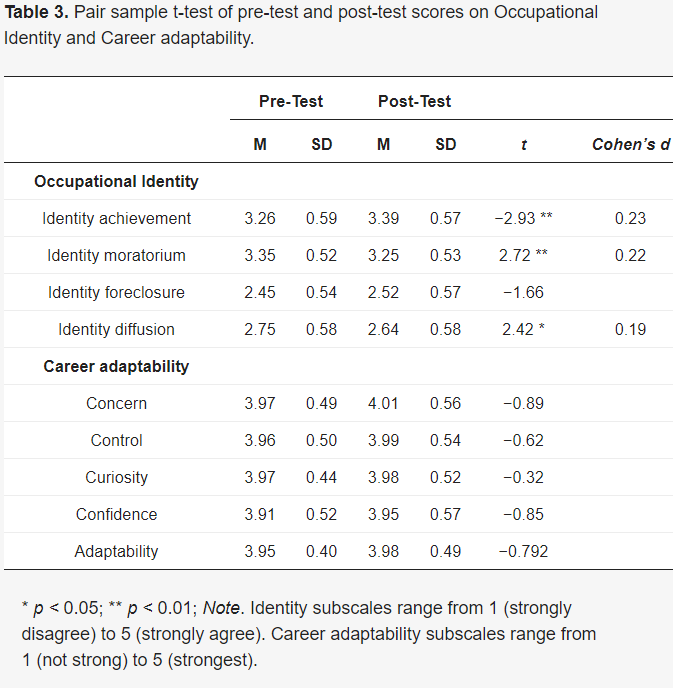

As stated previously, the variable-centered approach was used to examine the overall performance in this course. As shown by Table 3, significant improvement was found in occupational identity achievement (t = −2.93, df = 155, p = 0.00, d = 0.23), occupational identity moratorium (t = −2.72, df = 155, p = 0.00, d = 0.22) and occupational identity diffusion (t = −2.42, df = 155, p = 0.02, d = 0.19) from the pre-test to the post-test, but not in CSE (data not shown), identity foreclosure and career adaptability.

Personality Traits Groups

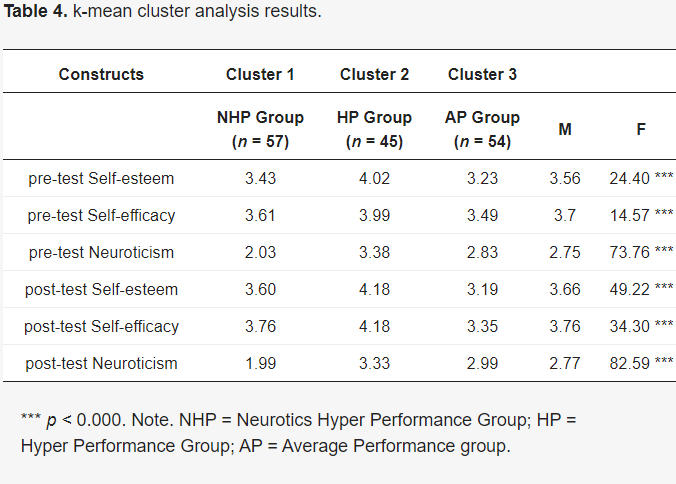

From the perspective of the person-centered approach, Table 4 illustrates the group means of the three CSE indicators. The procedure of selecting the number of clusters was based on the results of a preliminary hierarchical method, Ward’s algorithm which was recommended by previous literature [59,60]. The agglomeration schedule coefficients and dendrogram from Ward’s method results (data not shown) indicated three possible clusters. The k-mean clustering analysis indicated three groups of learners with distinctive personality traits pattern, including “Hyper Performance group (HP)”, “Neurotics Hyper Performance group (NHP)”, and “Average Performance group (AP)”.

Description of the Clusters

The first cluster was labeled as “Neurotics Hyper Performance group”. This group consisted of 36.5% (n = 57) of the sample. Students in this group were characterized by an emotionally unstable trait, a low score in Neuroticism (2.03; 1.99) with an average self-esteem (3.43; 3.60) and self-efficacy (3.61; 3.76) in both pre-test and post-test surveys.The second cluster was labeled as “Hyper Performance group”. This group comprised 28.8% (n = 45) of the sample and was characterized by the above average emotional stability (3.38; 3.33), self-esteem (4.02; 4.18) and self-efficacy (3.99; 4.18) scores. People who had contained these traits were well documented by previous literature which tended to have a better job or academic performance [61].The third cluster was named the “Average Performance group”. This group comprised 34.6% (n = 54) of the sample and was characterized by the average emotional stability (2.85; 2.99), self-esteem (3.23; 3.19) and self-efficacy (3.49; 3.35) scores.

The Impact of Personality Traits on Career Adaptability and Occupational Identity

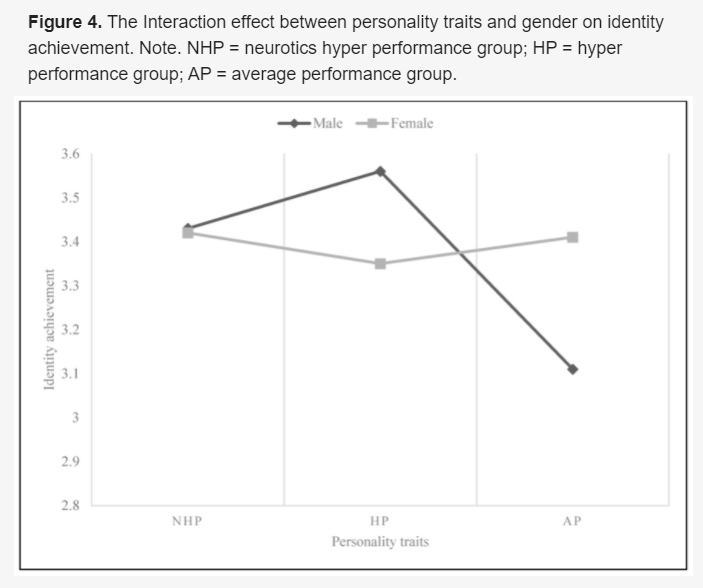

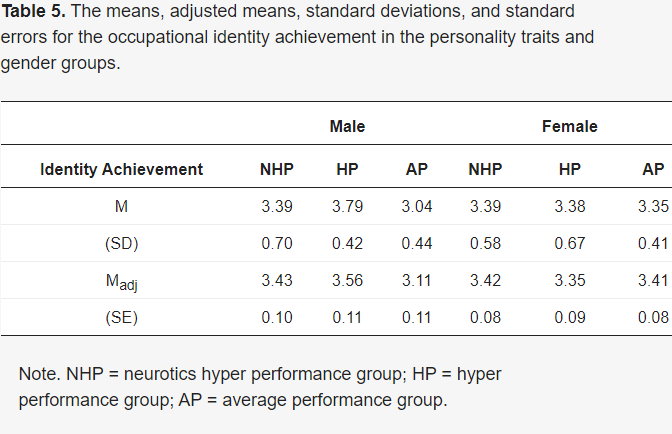

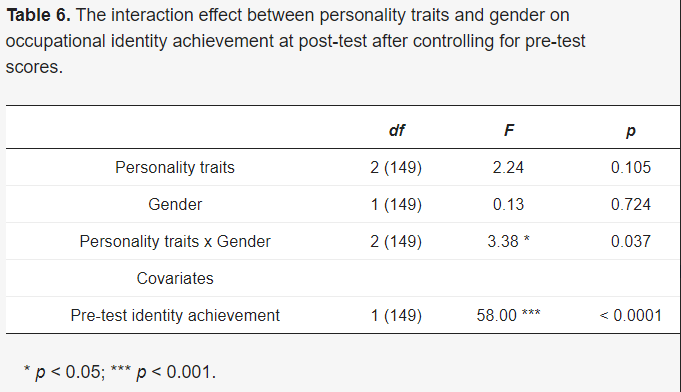

Levene’s test and normality test confirmed that all the significant pairs were equal variances and normally distributed (p > 0.05). After accounting for the pre-test scores as the covariate, the ANCOVA for personality traits on post-test occupational identity and career adaptability scores were found to have significant main effects and interaction effect (See Table 5 and Table 6). More specifically, there is no significant main effect in identity achievement F (2, 149) = 2.29, p > 0.05 but a possible interactions effect between personality traits with gender on identity achievement, F (2, 149) = 3.38, p < 0.05 whilst adjusted for pre-test scores (See Figure 4). A significant main effect was found on identity moratorium, F (2,152) = 3.80, p < 0.05. The post-hoc test showed that the HP group has a significantly lower score of moratorium (p < 0.05) than the NHP group. No significant difference (p > 0.05) was found between the AP group with the HP group and the NHP group.

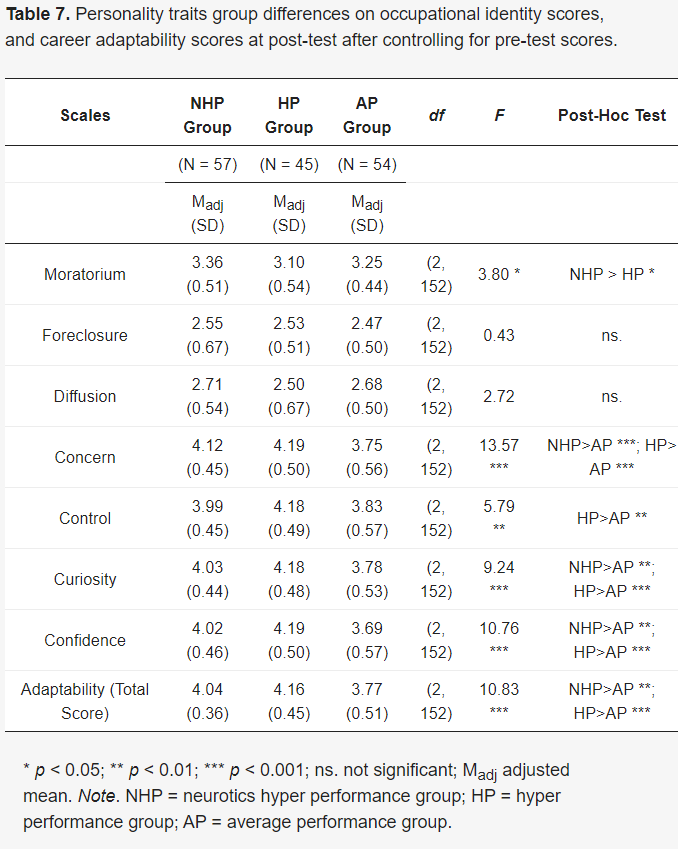

Apart from the occupational identity, the personality traits had main effects on the post-tests’ career adaptability (F (2, 152) = 10.83, p < 0.0001) and its subscales such as Concern (F (2, 152) = 13.57, p < 0.0001), Control (F (2, 152) = 5.79, p < 0.005), Curiosity (F (2, 152) = 9.24, p < 0.0001), and Confidence (F (2, 152) = 10.76, p < 0.0001) after controlling for pre-test scores (see Table 7). Post hoc tests showed that all the career adaptability traits in AP group were significantly lower that NHP and HP groups.

Discussion

The goal of the study was to examine whether using blended learning mode in a career course could enhance the career awareness of sub-degree students. The results could determine the CSE pattern in the effectiveness of the course. This study contributes to an understanding of how distinctive traits would affect the learning outcomes in a career course.

Effectiveness of the Career Development Course in Blended Learning Mode

With respect to the variable-centered approach, H1 (there will be a significant difference between pre-test and post-test occupational identity scores) was supported by the results. The results suggest that the proposed course was successful in improving the affective outcomes of the students, especially on their vocational identity. No significant improvement of career adaptability was observed. Therefore, H2 (there will be a significant difference between pre-test and post-test career adaptability scores) is rejected. Although this is the first time to conduct the course in a synchronous mode by incorporating Salmon [45] and Ryan [12]‘s works, a small effect size was found. When reviewing the recent studies on career programs, an average small effect size (d = 0.21) on vocational identity across delivery formats were reported [10,13]. The results of this study showed a similar level of small effect size (d = 0.21). However, from a class modalities perspective, this study (d = 0.21) contains a smaller effect size than traditional face-to-face format (d = 0.61) but a larger effect than self-paced computer format (d = 0.10) as reported by Whiston in 2017 [13]. There are two reasons to help explain our findings. First, we have more than 5 sessions in our course as evidence from the best practices highlighted that 4 or five sessions are enough to demonstrate the effect to participants [62]. However, these best practices did not state clearly whether there are differences in the numbers of the session between face-to-face and online settings. It would be useful to see whether a shortened blended learning course would still yield a similar effect. Second, our study showed a better effect than those of the self-paced computer-program. We hypothesized that this effect could be attributed to the use of ICT and interaction with the facilitators as was shown by Whiston [13] of the significant difference of the effect size between individual self-pacing program, individual and group program. Therefore, we suggest that the effectiveness of this re-formed career choice course is affected by the variation of numbers of sessions and delivery mode.The technology was shown to assist the learning and teaching. For example, pre-recorded videos would enable students to review the materials any time without physical barriers. The mock interview in blended learning mode was conducted and recorded through Zoom, the facilitators could evaluate their students’ performance and give comments any time. It was shown that the blended learning model was effective in delivering practical vocational training to students during the pandemic.

Occupational Identity of the Three Personality Traits Groups

H3 (There will be significant main effects of personality traits on post-test occupational identity scores controlling for pre-test scores) is supported by the data. Congruent with previous studies, our finding demonstrated the positive CSE traits were related to positive vocational identity [63,64] and partially related to career exploration [27]. Nevertheless, when examining these effects in the proposed course with controlled pre-test scores, the result only indicated an interaction effect between gender and personality traits groups. Interestingly, a cultural study showed that Hong Kong and Japanese samples reported a second lower and the lowest self-efficacy respectively when compared with other countries such as the UK, Korea, and France [43]. As noted by Cai et al. [42], Chinese assessed themselves less positively than Americans on cognitive self-evaluation (decision on one’s abilities, attributes and traits) but there was no difference in affective cognitive self-regards (emotions that direct how pleased or embarrassed of oneself). We assume that this variation of mechanism within Chinese might impair the validity of the CSE which therefore contributed infirm results in our study. Apart from culture findings, in this study, when an individual contains positive self-esteem, high self-efficacy, and emotional stable traits (HP group), the stage of identity achievement occurs frequently only in male respondents. Female participants did not show a significant difference in identity achievement from their personality patterns (No difference in NHP, HP, and AP groups). This result confirmed that multi-contextual factors such as gender and cultural differences would mediated the identity formation [65,66]. Empirical studies indicated a relatively long history of gender and cultural differences in self-esteem [67,68] and self-efficacy [43]. Similarly, the female students in this study reported lower self-esteem than the male students. While females often behave inferior self-evaluation during late adolescence, we assume that the gender and cultural differences would render the effects of CSE toward identity achievement further insignificant in this study.Furthermore, our findings suggested that despite the comparable levels of high endorsement of self-esteem and self-efficacy, a person who showed more neurotics traits (NHP > AP) was more likely to occur into the moratorium stage. The result showed the distress feelings of people in the mid-identity crisis among emotionally unstable persons. It is in line with the notion that “people in the moratorium stage generally experience more anxiety than other stages” [36]. More specific to the Hong Kong context, Xu and Lee (2019) reported that achievement anxiety had prolonged effects on secondary school students’ occupational identity [69]. Whilst our study highlighted the issue in Chinese samples, studies concerning the anxiety feeling of moratorium stages in career program in Western culture are limited, not to mention those in Chinese culture. Allison [70] explained that career program may benefit those adolescents with stressful occupational issues. When modern career development programs heavily stress practical exploration skills rather than inclusion of anxiety reduction components, our study conveys a key message for course practitioners to consider and be concerned about students’ affective outcomes during the program. Our result may shed light on course builders on the need for inclusion of anxiety reduction components, which is similar to the proposed components by Ryan, “Anxiety reduction”.Our findings echoed a cross-sectional study that demonstrated a weak association between CSE and career exploration domain [27]. The current study found that this model could be applied in examining the effectiveness of a career course in Hong Kong adolescent. According to the identity status theory, the moratorium is a stage that an individual explores identify alternatives for a career without commitment [36]. Our study confirmed that these clusters (NHP, HP, and AP groups) are valuable for understanding Hong Kong students’ identity status especially to those who had already explored or actively exploring career alternatives. The main effect in Identity Achievement was not detected, possibly due to the fact that most adolescents are still in the moratorium stage as reported by a recent qualitative study in Hong Kong [69]. Lastly, this study found no main effect in Identity Foreclosure and Identity Diffusion among NHP, HP, and AP groups. These findings supported that identity stages that were not relating to career exploration such as foreclosure are not psychological traits specific in the proposed model [15,34].

Career Adaptability of the Three Personality Traits Groups

When using the person-centered approach, H4 (there will be significant main effects of personality traits on post-test career adaptability scores controlling for pre-test scores) is supported by the data. However, the findings showed slight disagreement with the proposed career model of construction that emotional stability (AP and HP groups) may not be the main trait to facilitate strong career adaptability when an individual took part in synchronous career choice course. No difference on career adaptability performance was found between NHP and HP groups, differences occurred only within the HP and AP or the NHP and AP groups. Our findings are in agreement with some recent studies on Korean and Chinese employees that positive CSE is associated with expected work performance such as work engagement via career adaptability [71], despite the fact that these studies used different measurements. The finding also corroborates a recent Hong Kong study [38] that suggests self-esteem positively predicted career adaptability. In our study, neurotic students did not appear to be at a disadvantage in regard to their perceived adaptability of careers. This is in line with a recent Chinese study that indicated emotional stability did not have a direct effect on career adaptability in adult working setting [72]. Our findings further illustrate how CSE contributes to career adaptability at the primary stage, which explains the formation of vocational identity and vocational personality in the university.According to the career construction theory [32], career adaptability indicates that an individual’s readiness and resources could affect the way he/she handles work tasks, work trauma and transitions, and alter his/her personal-work environmental integration in some degrees. As people constructed their career using adaptive strategies often in line with individual personality traits, our results confirmed that the course helps students to better express their self-concept, aid their understanding of the social reality of work roles, and thus enable them to set realistic career goals. However, these effects could not be extended to their affective traits. A previous study [73] suggested a person with high self-efficacy usually experiences minor depressive feelings and anxiety. However, our study only found a very weak association between emotional stability and self-efficacy. It may be attributed to the typical emotional-suppressing behavior in the Eastern Asian collectivism culture when social harmony is prioritized and people tend to suppress their emotional expression in the workplace and schools [74,75]. This culture may deteriorate the path between emotion stability and perceived adaptive attitude. Different from the Western cultures, emotional regulation among Chinese people did not affect their psychological welling-being [76]. Considering negative emotion regulation in the workplace setting is an unspeakable rule in Chinese culture [77], it is hypothesized that self-esteem and self-efficacy are being more centered in the Asian populations for facilitating one’s adaptability in the social environment. This result may partly explain the higher career adaptability of Chinese as compared to their western counterparts [33]. As examination on career adaptability in Hong Kong is rare [38], our studies replicated the effect of Hong Kong students’ self-esteem onto their career adaptability. Although the CSE indicated how people consider themselves toward the situations, the variation of course effectiveness among the three personality types (NHP, HP, and AP) were existed and might provide meaningful messages for the practitioners. Thus, in a group that divides labor among its members, traits can be used to assign personalize training.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. The first limitation is the validity and reliability concerns of the core self-evaluation scale in Asian samples. In this study, the locus of control subscale failed to reflect the students’ beliefs, suggesting a possibility of a different self-evaluation mechanism of Asian students. Future research should focus on clarifying this concern in Asian samples. Second, despite the study results indicated the changes after participants received the proposed course, the certainty of the exact point at which an improvement in those affective outcomes begins have not been known. Our study did not consider the potential impact of environmental factors. More research is needed to compare those results with control group or waiting list design. Future research could incorporate the contextual factors such as social support. In addition, future research adopting a longitudinal study design would offer additional insights into the long-term effectiveness of the career choice course and how students cope with their occupational transition into the workforce. Another limitation is the exclusion of investigating the students’ attitude toward the blended learning approach. By adopting Salmon’s five-stage model, the present study neglected the association of learning model acceptance and career awareness. While eLearning acceptance findings indicated culture differences [78], future research should consider reporting the interactions between Asian students’ personality profiles, acceptance toward eLearning technologies, and other affective outcomes. The results would benefit the evaluation of the effectiveness of adopting a specific pedagogy involving technology framework for sub-degree students. Furthermore, to obtain more reliable results, future research could involve mixed research and experimental design.

Conclusions

This is the first study to combine the five-stage model and critical components for forging a blended, synchronous career course in Hong Kong during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study revealed that the course influenced the vocational identity formation only, but less so on career adaptability. However, when the results were controlled by pre-test performance and personality traits, the effects of career adaptability were highlighted. To address the personalized learning within this course, this study contributes to a better understanding of personality traits and its effects on a career choice course in Hong Kong during the COVID-19 pandemic. The outcomes from the positive CSE students, especially self-efficacy, self-esteem, and emotional stability have their areas of influence within the course. It reminded the educators to recognize learners’ personality traits when they evaluate courses in blended learning mode. Despite the results were not thoroughly supported by the previous literature, this paper showed the scope of cultural influence. The findings implicated that students’ emotional outcomes should be considered equally in a program when facilitators deliver the content. When a course builder designs a career course, there is also a need to add anxiety reduction session to the courses and related curriculum content. This study revealed that emotional regulation techniques are as important as facilitating students’ self-efficacy before they receive relevant career development skills. All these components are critical to establish the learning effectiveness of a career course. This study has taken a step in the direction of how a holistic whole-person development curriculum could benefit our young graduates whilst going through a challenging transition in the Hong Kong labor market.

References

- Consumer Search Hong Kong Ltd. Survey on Opinions of Employers on Major Aspects of Performance of First Degree Graduates in Year 2016—Executive Summary. Hong Kong. 2019. Available online: https://www.cspe.edu.hk/resources/pdf/en/Survey%20on%20Opinions%20of%20Employers%20on%20Major%20Aspects%20of%20Performance%20of%20First%20Degree%20Graduates%20in%20Year%202016%20-%20Executive%20Summary.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Shek, D.T.L. Nurturing holistic development of university students in Hong Kong: Where are we and where should we go? Sci. World J. 2010, 10, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, D.T.; Yu, L. General university requirements and holistic development in university students in Hong Kong. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Heal. 2016, 29, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, G. May the fourth be with you: Creating education 4.0. J. Learn. Dev. 2019, 6, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kintu, M.J.; Zhu, C.; Kagambe, E. Blended learning effectiveness: The relationship between student characteristics, design features and outcomes. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2017, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, B.; Kamaludin, A.; Romli, A.; Raffei, A.F.M.; DN A/L Eh Phon, D.; Abdullah, A.; Ming, G.L.; Shukor, N.A.; Nordin, M.S.; Baba, S. Exploring the role of blended learning for teaching and learning effectiveness in institutions of higher learning: An empirical investigation. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 24, 3433–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, B.; Toyama, Y.; Murphy, R.; Baki, M. The effectiveness of online and blended learning: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2013, 115, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, K.; Kovatcheva, E.P. Designing blended, flexible, and personalized learning. In Second Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education; Voogt, J., Knezek, G., Christensen, R., Lai, K.-W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 759–776. [Google Scholar]

- Boelens, R.; Voet, M.; De Wever, B. The design of blended learning in response to student diversity in higher education: Instructors’ views and use of differentiated instruction in blended learning. Comput. Educ. 2018, 120, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, R.J.; Miller, C.D. Using outcome to improve a career development course: Closing the scientist-practitioner gap. J. Career Assess. 2009, 18, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Ma, C.M.S.; Yang, Z. Transformation and development of university students through service-learning: A corporate-community-university partnership initiative in Hong Kong (Project WeCan). Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan Krane, N.E. Career Counseling and Career Choice Goal Attainment: A Meta-Analytically Derived Model for Career Counseling Practice; Loyola University: Chicago, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Whiston, S.C.; Li, Y.; Mitts, N.G.; Wright, L. Effectiveness of career choice interventions: A meta-analytic replication and extension. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.D.; Krane, N.E.R.; Brecheisen, J.; Castelino, P.; Budisin, I.; Miller, M.; Edens, L. Critical ingredients of career choice interventions: More analyses and new hypotheses. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 62, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. Life design: A paradigm for career intervention in the 21st century. J. Couns. Dev. 2012, 90, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.L.; Conkel, J.L. Evaluation of a Career development skills intervention with adolescents living in an inner city. J. Couns. Dev. 2010, 88, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.; Santos, A. The Impact of a college career intervention program on career decision self-efficacy, career indecision, and decision-making difficulties. J. Career Assess. 2017, 26, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Z.A.; Noor, U.; Hashemi, M.N. Furthering proactivity and career adaptability among university students: Test of intervention. J. Career Assess. 2020, 28, 402–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.D.; Krane, N.E.R. Four (or five) sessions and a cloud of dust: Old assumptions and new observations about career counseling. In Handbook of Counseling Psychology, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed, R.A.; Kamsin, A.; Abdullah, N.A.; Zakari, A.; Haruna, K. A systematic mapping study of the empirical MOOC literature. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 124809–124827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pordelan, N.; Sadeghi, A.; Abedi, M.R.; Kaedi, M. Promoting student career decision-making self-efficacy: An online intervention. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 25, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillahunt, T.R.; Ng, S.; Fiesta, M.; Wang, Z. Do Massive Open Online Course Platforms Support Employability? In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, ACM, February 2016; Volume 27, pp. 233–244. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1145/2818048.2819924 (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Judge, T.A.; Bono, J.E. Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—Self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—With job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swider, B.W.; Zimmerman, R.D. Born to burnout: A meta-analytic path model of personality, job burnout, and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, A.L.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, K.; Morrison, H.M.; Jorgensen, D.F.; Ma, Q. Trait expression through perceived job characteristics: A meta-analytic path model linking personality and job attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 112, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; Judge, T.A. Core self-evaluations: A review of the trait and its role in job satisfaction and job performance. Eur. J. Pers. 2003, 17, S5–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A.; Herrmann, A.; Keller, A.C. Career adaptivity, adaptability, and adapting: A conceptual and empirical investigation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 87, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z. Core self-evaluation and career decision self-efficacy: A mediation model of value orientations. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 86, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E.; Rubini, M.; Luyckx, K.; Meeus, W. Identity Formation in early and middle adolescents from various ethnic groups: From three dimensions to five statuses. J. Youth Adolesc. 2008, 37, 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wu, C.; Wang, P.; Li, H.-H. The influence of personality traits on nurses’ job satisfaction in Taiwan. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2010, 57, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.-M.; Yu, K. When core self-evaluation leads to career adaptability: Effects of ethical leadership and implications for citizenship behavior. J. Psychol. 2019, 153, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savickas, M.L. Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work, 2nd ed.; Brown, S.D., Lent, R.W., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M.L.; Porfeli, E.J. Career adapt-abilities scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Career adaptability: A meta-analysis of relationships with measures of adaptivity, adapting responses, and adaptation results. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 98, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. Youth: Identity and Crisis; W. W. Norton Company: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Marcia, J.E. Development and validation of ego-identity status. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1966, 3, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgosa, J. Development and validation of the occupational identity scale. J. Adolesc. 1987, 10, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, T.; Yuen, M.; Chen, G. Career adaptability, self-esteem, and social support among Hong Kong University students. Career Dev. Q. 2018, 66, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, C.; Fay, D.; Zapf, D.; Frese, M. A State-trait analysis of job satisfaction: On the effect of core self-evaluations. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 55, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Van Vianen, A.E.M.; De Pater, I.E. Emotional stability, core self-evaluations, and job outcomes: A review of the evidence and an agenda for future research. Hum. Perform. 2004, 17, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-H.; Griffin, M.A. Longitudinal relationships between core self-evaluations and job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Brown, J.D.; Deng, C.; Oakes, M.A. Self-esteem and culture: Differences in cognitive self-evaluations or affective self-regard? Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 10, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, U.; Doña, B.G.; Sud, S.; Schwarzer, R. Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2002, 18, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsin, A.; Xie, Y. Explaining Asian Americans’ academic advantage over whites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8416–8421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.Y. The influence of culture on parenting practices of east Asian families and emotional intelligence of older adolescents: A qualitative study. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2010, 31, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, K.-T. The Myth of Asian American Success and Its Educational Ramifications. 1980. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED193411 (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Kirkup, G. E-Tivities. The Key to Active Online Learning; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Salmon, G.; Nie, M.; Edirisingha, P. Developing a five-stage model of learning in Second Life. Educ. Res. 2010, 52, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.L. A theory of vocational choice. J. Couns. Psychol. 1959, 6, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauta, M.M. The development, evolution, and status of Holland’s theory of vocational personalities: Reflections and future directions for counseling psychology. J. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 57, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tien, H.-L.S.; Wang, Y.-C.; Chu, H.-C.; Huang, T.-L. Career adapt-abilities scale—Taiwan form: Psychometric properties and construct validity. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 744–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Locke, E.A.; Durham, C.C. The dispositional causes of job satisfaction: A core evaluations approach. Res. Org. Behav. 1997, 19, 151–188. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Erez, A.; Bono, J.E.; Thoresen, C.J. The core self-evaluations scale: Development of a measure. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics®. Qualtrics; Qualtrics: Provo, UT, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmans, J.; Wille, B.; Schreurs, B. Person-centered methods in vocational research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 118, 103398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.C.; Hoffman, M.E. Variable-centered, person-centered, and person-specific approaches: Where theory meets the method. Organ. Res. Methods 2018, 21, 846–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. Proc. Fifth Berkeley Symp. Math. Stat. Probab. 1967, 1, 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Steinley, D. Local optima in k-means clustering: What you don’t know may hurt you. Psychol. Methods 2003, 8, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, G.W.; Cooper, M.C. Methodology review: Clustering methods. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1987, 11, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, N.J.; Hambrick, D.C. Conceptualizing executive hubris: The role of (hyper-)core self-evaluations in strategic decision-making. Strat. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Career decision making, fast and slow: Toward an integrative model of intervention for sustainable career choice. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 120, 103448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A. Vocational identity as a mediator of the relationship between core self-evaluations and life and job satisfaction. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 60, 622–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounsbury, J.W.; Levy, J.J.; Leong, F.T.; Gibson, L.W. Identity and personality: The big five and narrow personality traits in relation to sense of identity. Identity 2007, 7, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N.J.; Madsen, E. Contextual influences on the career development of low-income African American youth: Considering an ecological approach. J. Career Dev. 2007, 33, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Kim, D.W.; Lee, K.-H. Contextual influences on Korean college students’ vocational identity development. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2016, 17, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, K.C.; Hyde, J.S.; Showers, C.J.; Buswell, B.N. Gender differences in self-esteem: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 470–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleidorn, W.; Arslan, R.C.; Denissen, J.J.A.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Gebauer, J.E.; Potter, J.; Gosling, S.D. Age and gender differences in self-esteem—A cross-cultural window. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 111, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Lee, J.C.-K. Exploring the contextual influences on adolescent career identity formation: A qualitative study of Hong Kong secondary students. J. Career Dev. 2019, 46, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berríos-Allison, A.C. Family influences on college students’ occupational identity. J. Career Assess. 2005, 13, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K.; Lee, K.-H. Core self-evaluation and work engagement: Moderated mediation model of career adaptability and job insecurity. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Dai, X.; Gong, Q.; Deng, Y.; Hou, Y.; Dong, Z.; Wang, L.; Huang, Z.; Lai, X. Understanding the trait basis of career adaptability: A two-wave mediation analysis among Chinese university students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 101, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schouten, A.; Boiger, M.; Kirchner-Häusler, A.; Uchida, Y.; Mesquita, B. Cultural differences in emotion suppression in Belgian and Japanese couples: A social functional model. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, A.; Moser, J.S.; Kitayama, S. Culture shapes electrocortical responses during emotion suppression. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2013, 8, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, J.A.; Perez, C.R.; Kim, Y.-H.; Lee, E.A.; Minnick, M.R. Is expressive suppression always associated with poorer psychological functioning? A cross-cultural comparison between European Americans and Hong Kong Chinese. Emotion 2011, 11, 1450–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, K.Z.; Wong, C.-S.; Song, J.L. How do Chinese employees react to psychological contract violation? J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Zhou, R.; Li, S. Do cultural differences affect users’ e-learning adoption? A meta-analysis. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 52, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

This article is governed by: